The patchwork of digital tax proposals in Europe

by Inline Policy on 09 Nov 2018

While discussions continue on the European Commission’s proposals for a harmonised Digital Services Tax, a number of different approaches to taxing online service providers and platforms is emerging across Europe. With the UK the latest EU country to consider going it alone, we look at who is proposing what when it comes to digital services taxes.

How to tax some aspects of the digital economy is an issue that has been increasingly vexing policymakers across the globe. At the heart of this question are issues that are common to the taxation of all multinational corporations, which have been the subject of OECD discussions for a number of years. The issues and the political concern around them have been supercharged by the growth of the large tech firms. The question of how much tax multinational tech companies pay, and where they pay it, has now become a perennial story for the media and a popular campaigning issue for politicians from across the political spectrum.

An obvious problem with no obvious solution

The problem is easy to understand with companies like Apple and Amazon breaking through the unprecedented $1 trillion valuation (and Alphabet not far behind), while corporate tax receipts from these companies in well-developed digital economies are smaller than those from smaller companies with more traditional business models. While the problem may be easy to understand, the possible solutions are much more complex, as they go to the heart of how the global tax system operates and require international negotiations and changes to tax treaties.

With OECD negotiations on the issue taking years and showing no signs of significant progress, political patience is running out and an increasing number of governments are either considering or implementing their own approach to taxing parts of the digital economy. These governments are all taking different approaches, based on the key concerns for their economy and their society. Some EU-based examples include:

- Hungary first introduced a tax on advertising, which included online advertising, in 2014. The tax was amended after the European Commission ruled that it breached EU rules. The tax is not applied on entities with revenues exceeding HUF100 million who must pay a 5.3% tax on advertising shown in the Hungarian language, regardless of where the publisher and advertiser are located.

- Since January 2018 digital platforms that provide transport or accommodation intermediation inside Slovakia have been required to establish a place of permanent establishment within the country and so become liable for corporation tax.

- Italy had planned to introduce a ‘web tax’ that would add 3% to sales of “intangible digital products”, such as online advertising. The tax was due to come into force in January 2019, but the new government has now said it will wait for progress on an EU-wide solution.

EU proposals for a Digital Services Tax

Instead of this piecemeal approach by different countries, some European governments are pressing for a harmonised EU-wide approach to minimise competition between Member States and to make faster progress than the OECD. The French President Emmanuel Macron has been a key proponent of this approach with a number of other countries voicing their support. In March 2018 the European Commission responded to this pressure from politicians with proposals for both a short-term and a longer-term approach, which the EU could adopt while it awaits a global solution being agreed at the OECD.

The Commission’s long-term approach involves a reform of corporate tax rules to enable Member States to tax profits that are generated in their territory, even if a company does not have a physical presence there. In essence a digital platform meeting certain criteria would be deemed to have a taxable “digital presence” even if it did not have a permanent establishment in a Member State, thereby making the company’s profits subject to tax in that country. There would also be changes to how profits generated in Europe are allocated between Member States in order to ensure a link between “where digital profits are made and where they are taxed”. It is planned that these measures would be integrated into the scope of the Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base (CCCTB), which is a broader proposal from the Commission on allocating profits of large multinational groups and not just restricted to the digital sector.

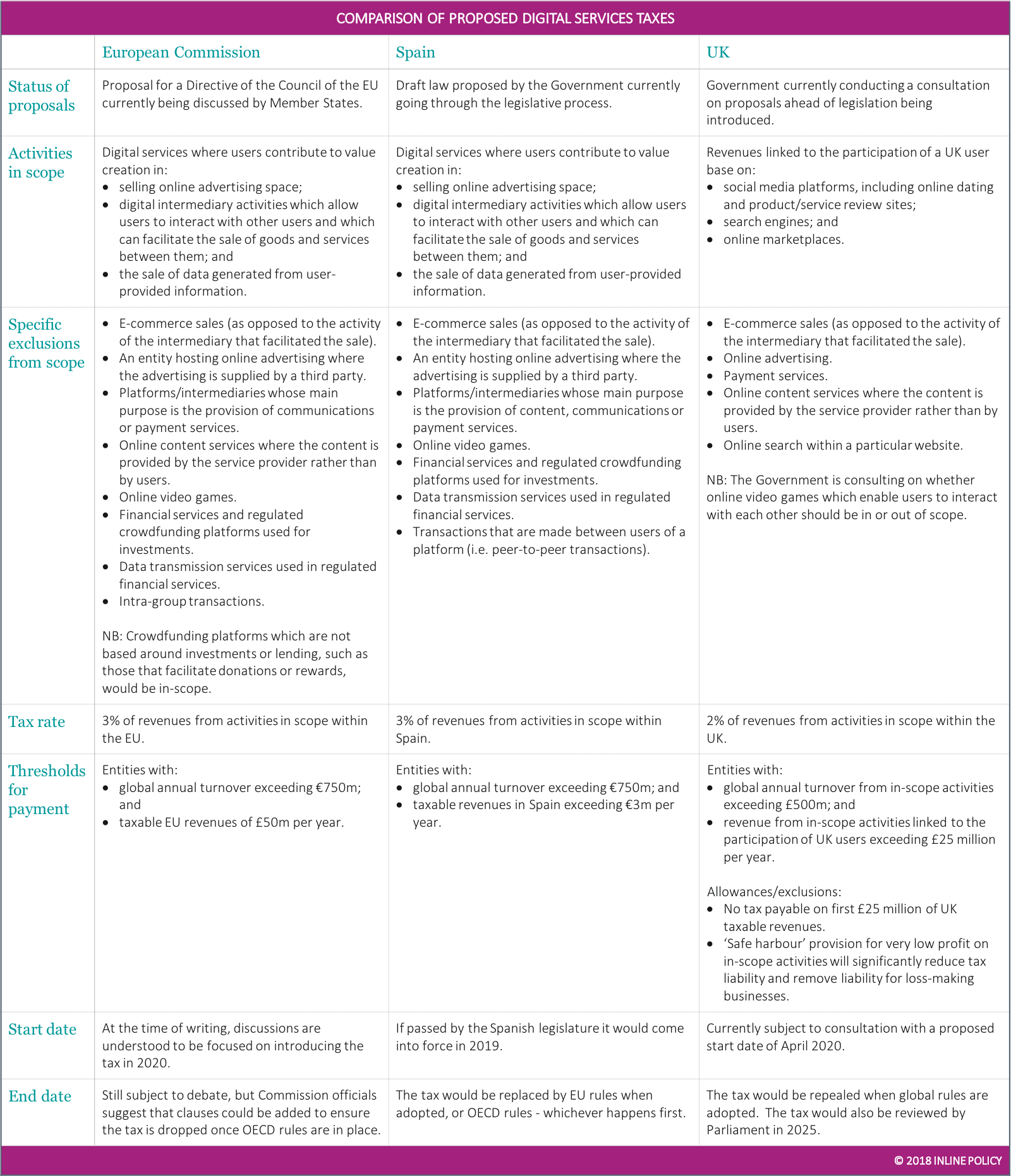

Given the complexity of negotiating the significant changes in the long-term approach, the Commission’s short-term proposal is an “interim tax” on revenues for certain digital services. The Commission says its proposals are aimed at avoiding “a patchwork of national responses” which would be damaging to the Single Market. The key elements of the short-term proposals are set out in the table below.

The drive to achieve an EU agreement received significant support from Austria’s Chancellor Sebastian Kurz as Austria took on the rotating Presidency of the Council of the EU and it seems that some progress has been made in the EU proposals. Nevertheless, the required unanimous support of all EU Member States governments still seems unlikely given the entrenched positions of some countries who either benefit from the current arrangements or fear they will lose out under the Commission’s longer-term proposals. While there have been some suggestions that the enhanced co-operation process, whereby a majority of Member States push ahead with a common approach, this would not achieve the aim of a common EU tax rate, as it would not apply in those countries who disagreed with the tax.

The EU’s proposals have been criticised by the OECD, which stated that they would be “likely to generate some economic distortions, double taxation, increased uncertainty and complexity, and associated compliance costs for businesses operating cross-border and, in some cases, may potentially conflict with some existing bilateral tax treaties.” There has also been strong criticism from the US Government, which sees such taxes as unfairly targeting American companies. The prospect of retaliatory action from the Trump Administration is therefore a considerable risk in the minds of European policymakers, in particular Germany which is said to be concerned about retaliatory action against its car industry.

Comparing proposals for Digital Services Taxes

With progress seemingly slow at both the OECD and the EU, some countries are looking to introduce their own ‘digital services tax’. In October the Spanish Government published a draft bill, less than two weeks later UK Chancellor Philip Hammond announced that he would bring forward his own proposals for a revenue-based tax with a narrower focus than the European Commission’s proposals.

The key elements of the EU’s interim proposals, Spain’s draft law and the UK’s proposals that are currently being consulted on, are set out in the table below. As can be seen, the Spanish draft law is very similar to the European Commission’s proposals in many – but not all – respects. In contrast, the UK has taken a different approach in terms of the scope of the tax and the level of the tax. The differences between approaches are most apparent in the specific exclusions from the scope.

What happens next and what can businesses do about it?

Each of these digital services tax proposals are subject to ongoing debates and are continuing to be developed and adapted. For each proposal there are still many details that remain open and so it is unclear what the eventual impact of each will be. Any company with a significant digital business needs to pay close attention to these discussions, active participation in consultations and contact with policymakers may be required to ensure that they are not inadvertently captured within the scope of the proposed laws.

In the meantime, those companies which are clearly being targeted by the scope of the different pieces of legislation are already strongly lobbying against the proposals. It will be interesting to see if their stance shifts as the legislative process continues in order to expand the scope and avoid being singled out compared to their digital or non-digital competitors.

If you would like to gain a better understanding of these proposals and how they might affect your business, then please get in touch.

Topics: European Politics, E-commerce, Crowdfunding, UK politics, Adtech, Economic policy, Big Tech, David Abrahams, Tax

Comments