Consumer protection legislation in the connected future

by Inline Policy on 02 Mar 2020

The spread of tiny chips into more and more everyday items promises a cumulative leap in convenience for consumers and productivity for businesses. Yet as ever more consumer devices become hooked up to the internet and the line between hardware and software blurs, the question of consumer protection and the need for new consumer regulations will receive greater attention.

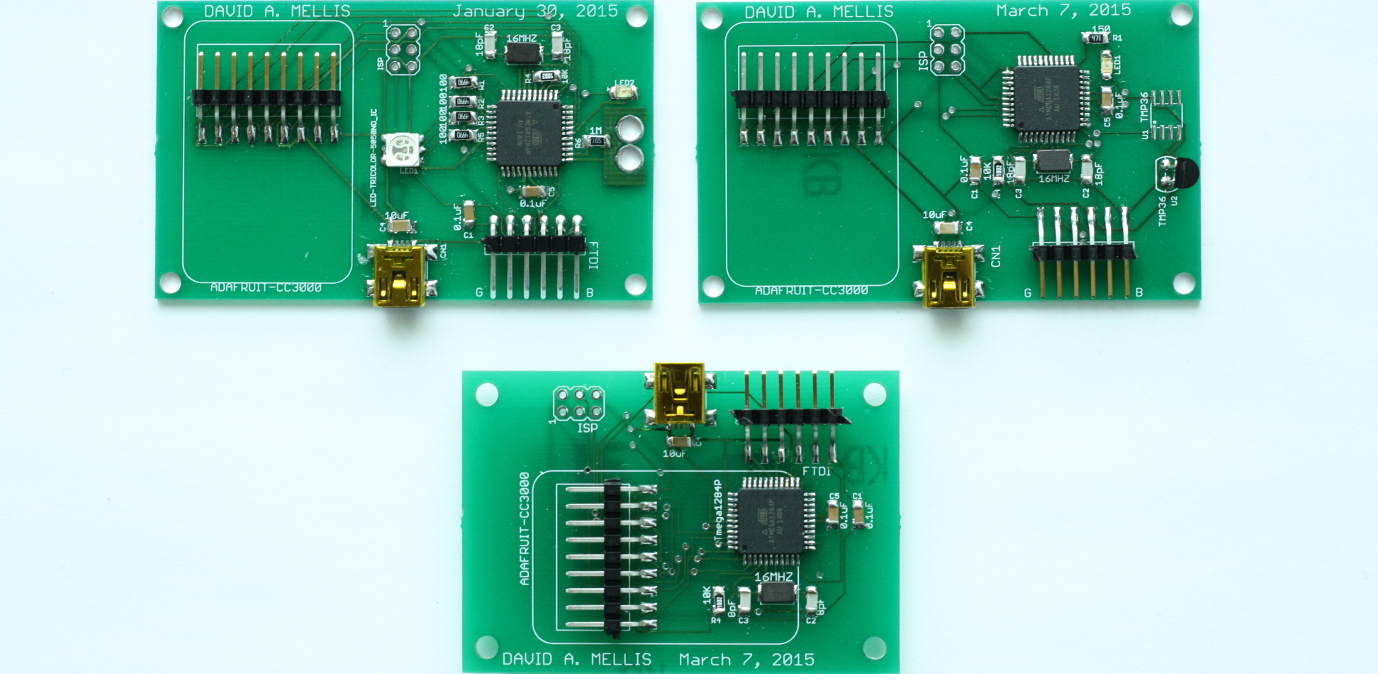

We are witnessing the next stage of the computer revolution. Just as large supercomputers gave way to PCs and laptops, which in turn gave way to smartphones, the existence of ever smaller and less expensive chips means that increasing numbers of goods are becoming minicomputers. This phenomenon is loosely defined as the Internet of Things (IoT). Arm, one of the world’s leading chip-design firms, estimates that there will be over one trillion IoT chips by 2035, inserted into everything from clothes to cows.

The benefits of such unprecedented connectivity are individually small but cumulatively huge. Smart traffic systems will reduce congestion and support autonomous driving, helping both the environment and productivity in the process. For the individual consumer, convenience will become ever more achievable. Google, Amazon and Apple’s home management systems are increasingly ubiquitous, whilst cooking instructions can now be relayed to an oven simply by scanning a food label through a Whirlpool app.

Hardware v software

Traditional hardware is increasingly reliant on embedded software in order to operate. It is no longer easy to differentiate the tangible from the intangible, which poses some difficult questions when it comes to consumer protection. Existing consumer laws are designed to reflect consumers’ expectations that goods will function as advertised and, in the case of expensive items, will last for a reasonable amount of time. In effect, present day regulations tip the scales in favour of the consumer by imposing stringent obligations on manufacturers to ensure their goods are of a certain (high) standard. They are also fairly easy to enforce and monitor, because goods are tangible.

The rise of software-dependent goods tends to favour instead the producer, since software is often licensed rather than sold.

During Hurricane Dorian in the US last summer, Tesla vehicle owners in the storm’s path were suddenly able to drive farther on a single battery charge. Cheaper Tesla models normally have parts of their batteries disabled by the car’s software to limit their range but during the storm, the company was able to temporarily remove those restrictions.

Meanwhile, John Deere, a high-tech tractor manufacturer in the US, has faced controversy over software restrictions that prevent farmers from repairing their tractors themselves and argued that, in some cases, buyers are not actually buying a tractor but merely paying for a licence to operate one. Indeed, the outrage caused by this case suggests that consumers continue to believe that they are buying goods, even when these are highly dependent on software, and assume the law will protect them accordingly.

This includes the expectation that goods will continue to function as advertised for a reasonable amount of time, potentially setting up conflict in a world of software-dependent devices where consumers will continue to expect big-ticket items such as washing machines to function for over ten years, when the norm for software updates is half that time.

Put bluntly, if a hardware manufacturer loses interest in a product or wants to nudge consumers to buy a newer model, they could decide to stop issuing software updates, thereby rendering many goods less useful. It is in this context that Apple and Android have faced greater scrutiny, with Apple being accused of deliberately slowing down older versions of the iPhone to nudge customers to buy newer devices. Google only currently guarantees Android software updates for around two years.

Prepare for new consumer protections

All this suggests that new legislation to bridge the gap between protections for tangible and intangible goods could be on the way soon. Under current legislation, there are two separate regimes that coexist increasingly uneasily.

For example, in England and Wales, customers buying an iPhone are entitled to a free repair or replacement, discount or refund for defective hardware for up to six years after delivery of said goods (in Scotland the period is five years).

Similarly, California has followed other US states in introducing a Right to Repair Bill that would compel electronics manufacturers to make manuals, guides and other repair information publicly available so that consumers are not reliant on the manufacturer to repair their device, often at a premium.

However, there is no similar Right to Repair Bill for software. This distinction becomes increasingly blurred when software controls all a hardware’s functions, as in the case of John Deere tractors. In addition to the difference in protections for defective hardware and software, there are no current laws stipulating that an electronics company must provide software updates for a minimum amount of time. A manufacturer could decide to stop providing software updates after one year, seriously impacting the functioning of their product as advertised, and consumers would have limited right of redress. This may prove to be untenable as the distinction between hardware and software becomes meaningless in more and more products.

Moves to introduce new consumer protection laws of this kind for connected devices would also be in line with the general direction of policy towards greater consumer protections and a desire to create better-informed consumers. For instance, earlier in the year the UK Government announced new legislation to improve the security standards of IoT devices. The new measures include an obligation on manufacturers to explicitly state at the point of purchase the minimum amount of time that a product will receive security updates. The Government has promised additional regulations. Such rules would also tally with the EU’s push to set the global standard for consumer protection and could prevent European consumers from being reliant on future software updates from US and Chinese giants.

Many argue that further protections for connected devices are unnecessary, pointing out that software-reliant goods are covered by existing consumer protection laws for goods in the UK, including the Consumer Rights Act 2015. Yet this only applies to defective software, rather than a decision by the producer to stop issuing updates, even though the effect – the product not functioning as advertised – is the same. As this gap in regulation is exposed by ever more products, don’t be surprised if more companies become swept up in a new wave of consumer protection legislation.

Topics: UK politics, Regulation, Technology, Politics

Comments