What’s next for the digital marketing sector, post-GDPR?

by Inline Policy on 09 Sep 2020

Even with the UK’s digital marketing sector still grappling with the aftershocks of GDPR implementation in 2018, further regulation has been brewing over recent months. The UK Government undertook a consultation on online advertising earlier this year, which it is expected to respond to imminently with new policies in mind. Indeed, it seems if not 2020, then 2021 might be the next watershed moment for the industry. Drawing from recent developments over this summer - including the latest proposals of the Competition and Markets Authority, and the evaluation of the current framework in a DCMS-commissioned study – this blog post will map out what this new wave of regulation might look like.

On 1 July 2020, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) published a market study and report on online platforms and digital advertising, following a year of research into how online advertising revenues drive the business models of major online platforms. A week later, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) published a study they had commissioned to assess the regulatory initiatives directed at online advertising issues, and subsequent recommendations. The significant degree of crossover between these two documents, despite their derivation from different authorities and slightly different points of focus, suggests that certain changes to the regulatory framework may be imminent.

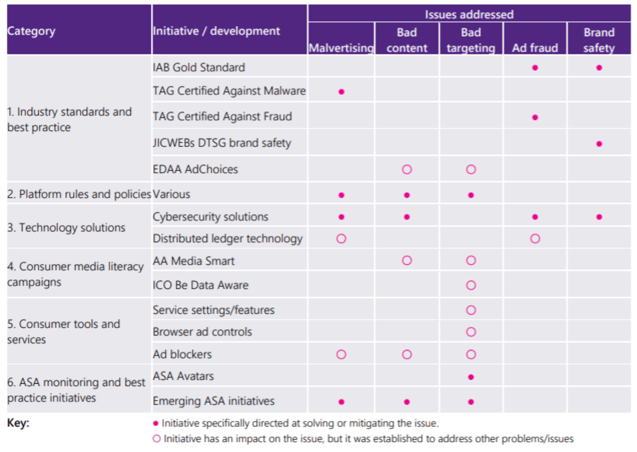

Currently, digital advertising is subject to a system of largely self-regulation in the UK. The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) is the lead regulator responsible for enforcing rules on advertisements and marketing communications, but relies on a system of reputational sanctions and, if necessary, escalating to other bodies that have statutory powers. Meanwhile, the industry itself has developed standards and common practices in response to concerns about harmful advertising. The DCMS-commissioned report mapped out the existing industry and regulatory initiatives in the below table:

Although this is fairly comprehensive, this framework still contains important gaps. Both the CMA and the DCMS reports came to the same conclusion that further Government and regulatory action is required in order to achieve real efficacy. This blog post will not scrutinise what products are advertised (which is a hot topic in itself, with Google recently banning ads for spyware and surveillance products, and the World Health Organization calling for more regulation of alcohol advertising), but will instead look at three key areas that may change how digital advertising is conducted going forwards.

1. Competitive practices with online platforms

One of the focuses of the debate thus far has been the oversight of online platforms and the revenues they generate through digital advertising. The DCMS-commissioned report acknowledges that while platforms’ policies and guidelines usually align with existing UK rules on advertising (as per the CAP Code), “there could be more clarity about how these policies and guidelines are enforced” as the Code does not technically apply to platforms – only advertisers.

The CMA goes further, and argues in its report that platforms like Google and Facebook, which it admits had originally grown by virtue of fairly offering valuable services, are now protected from competition by the nature of the digital market, which favours economies of scale, network effects and unprecedented data access. Together, these two platforms now receive over 80% of the digital advertising expenditure in the UK, and the CMA argues that prior legislation, like the GDPR, only acts as a justification for restricting access to valuable data for third parties while retaining it for the platforms’ own use and “entrenching their market power”.

As a result, the CMA has recommended to Government that a new pro-competition regulatory regime be established for digital marketing, headed by a Digital Markets Unit, and governed by high-level principles of fair trading, open choices, trust and transparency. In line with this, every company that is deemed to have ‘strategic market status’ would be required to have its own tailored code that would have a statutory basis (and thus be enforceable by the Unit). In the interim, the CMA has already gone ahead and established (in conjunction with fellow regulators Ofcom and the Information Commissioner’s Office) a Digital Markets Taskforce, which will lay down the blueprints for the new body and regime and report back to Government at the end of 2020. None of this is entirely new – much of it derives from the government-instigated Furman review last year, which argued that action needed to be taken to open up digital markets and avoid a monopoly of ‘gatekeeper’ platforms. But it seems the wheels are beginning to turn.

In July 2020, the competition regulator also proposed specific measures that should be explored, in particular relating to Google (and opening up its click-and-query data to rival search engines) and Facebook (e.g. increasing its interoperability with competing social media platforms and giving consumers the choice about whether to receive personalised advertising).

2. Targeting, such as discrimination and inappropriate targeting

Another key concern regards the practice of targeting. Although the industry argues that this has benefits for consumers (i.e. they will not be bothered with ads that are not relevant to them), others argue that “it has fuelled surveillance capitalism”. The DCMS-commissioned report seems to have some sympathies with these views, in particular raising red flags around discriminatory targeting which becomes “a problem if the product or offer advertised should be accessible to all, or discrimination is on the basis of protected characteristics”. Similarly, if demographic indicators are used to reinforce stereotypes, this could become illegal discrimination, especially if done on the basis of protected characteristics such as race or religion.

Although industry has already taken steps to try to allay these fears, these measures are not regarded as entirely successful in policymakers’ eyes; for example, while Facebook removed over 5,000 targeting options in August 2018 (to limit the ability for advertisers to exclude audiences based on attributes such as ethnicity or religion), a class action lawsuit was still filed against Facebook in October 2019, alleging that older and female Facebook users were denied advertisements about financial services. It therefore seems plausible that regulators may pursue greater and more stringent regulatory oversight of these practices.

3. Consumer protection framework

A number of mechanisms for consumers reporting ads they feel to be inappropriate or inaccurate already exist, including going directly to the ASA and/or reporting the ad to the platform hosting it. The figures from recent years illustrate that these mechanisms are used: the ASA received 16,059 complaints about online ads in 2018, 48% of all complaints and a 41% year on year increase.

However, the DCMS report asserts that the lack of a ‘one-stop shop’ solution makes the process complex and intimidating to consumers. Instead, there exists “a confusing patchwork of reporting methods”, which stems at least in part from regulatory overlap when it comes to digital advertising.

The report outlines the roles of the ASA, the CMA, the ICO, Trading Standards, Citizens Advice, and the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau, all of which make for a complex jigsaw of a regulatory landscape. This characteristic also compounds concerns about consumer protection because it muddles the process of enforcement action, following the report being made. Going forward, it is foreseeable that the proposed Digital Markets Unit could provide the remedy to this issue, depending upon how it is implemented in practice.

In addition to this, the DCMS report states that “in many cases, the incentives to report bad advertising are likely to be low and consumers may not bother, especially if the level of harm or financial loss at an individual level is low, and there is no assurance that the complaint will be dealt with in an appropriate way”.

But these factors only even become issues if the consumer realises that they are the subject of harmful advertising – something which several government and regulators’ studies have shown not to be the case. For example, Ofcom’s Children Media Lives (2020) found that while children could identify ads in an online platform, they believed that this advertising was random. Incorporating this factor makes policymakers all the more anxious for a more stringent consumer protection framework when it comes to digital advertising. It is therefore likely that the consumer literacy campaigns that seek to educate the public about potential harms will be ramped up in the future.

Will consensus translate into accelerated change?

As the CMA notes, whilst its recommendations are “UK-focused, many of the problems that the CMA has identified are international in nature”. It is true; in spite of the UK leaving the EU, key legislative files like the Digital Services Act package (which seek to foster competition while affording digital protections) are calling for a very similar direction of travel to that being proposed in the UK. This broad consensus by policymakers both within and outside of the UK seems to suggest that the digital marketing industry should brace itself for new regulatory developments sooner rather than later. This may well come about most notably when the DCMS responds to its consultation on online advertising from earlier this year. If so, GDPR may be just the beginning.

Topics: Immersive Tech, Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR), Technology

Comments