Government must take a holistic view of XR beyond just gaming

by Inline Policy on 24 Jun 2020

The Government responded earlier this month to the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) Select Committee’s recommendations on ‘immersive and addictive technologies’. While it establishes a commitment to proportionate and enabling regulations for the virtual (VR) and augmented reality (AR) industry, both the Committee and the Government miss a trick by failing to see beyond initial gaming applications. Greater understanding of the broad scope that the technology potentially offers will be critical if the UK is to sustain its status as a leader in the space.

Throughout 2019, the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee took evidence from various stakeholders, in an attempt to “examine the development of immersive technologies such as virtual and augmented reality, and the potential impact these could have”. Committee Chair at the time, Damian Collins MP, said at the outset that this exercise was driven by an acknowledgement that VR and AR was already an integral part of a range of sectors, including film and simulated training. This was an encouraging statement of intent. However, as the inquiry unfolded over the course of the year, it became disappointingly clear that the focus would be almost exclusively dominated by the technology’s use in gaming. While there is no denying that immersive tech (XR)’s initial development has ridden on the coat tails of gaming investment, failing to see beyond this lacks foresight, and an appreciation of the market as it already stands.

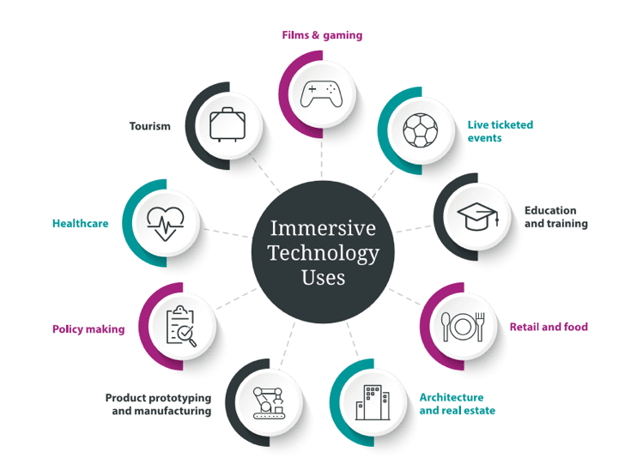

In fact, 50% of worldwide spending on VR and AR already derives from commercial applications (led by retail and manufacturing), and this is forecast to grow even further to 68.8% in 2023. For an insight into specific use cases, ranging from allowing prospective customers to visualise furniture purchases in their living rooms through to boosting accuracy when manufacturing complex engineering concepts, you can read our report here.

The diversity of these use cases has been acknowledged by other governments which are also vying for pole position when it comes to leading XR adoption. In particular, the Chinese Ministry of Industry and Information Technology published a dedicated strategy a year and a half ago, which clearly stated the Chinese Government’s ambitions. The strategy committed support for the introduction of VR and AR in a range of different use cases, including manufacturing, education, culture, health, retail and real estate.

So why is there a lingering perception in the UK of immersive technology as an asset of the gaming sector alone? At least in part, this attitude can be attributed to a persistent lack of awareness about the scale of the potential that the technology offers – at least among many MPs. While it does not go unseen by all parliamentarians (in the last month, Lord Wei recently implored the Government to consider the use of virtual reality in judicial processes, while Lord Taylor pressed the Government on its plans to use VR in NHS hospitals for Covid-19 training), much of the expertise on this subject remains holed up with DCMS officials and the Digital Catapult, the UK’s advanced digital technology innovation centre. However, without the spotlight afforded by high profile policy processes (such as select committee inquiries), the enabling regulatory framework that is required for XR across the board continues to falter.

A prime example of this is the tangible outcomes that we will now see materialise from the findings of the DCMS report: there will be limited benefits for the XR industry broadly, precisely because tackling the gaming sector has been the primary focus. The Government has pledged further research into the impact of video games on behaviour, through a series of workshops led by DCMS and UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) with academia and industry; and there will be a call for evidence on loot boxes in gaming, which may inform future revisions of the Gambling Act. One other sub-sector that stands to benefit is e-sports, with Government committing to a series of ministerial roundtables to support the development of this area in the UK. But there is nothing about the growing use of XR in other industries such as healthcare, tourism and architecture, to name but a few.

All of this said, the tone of the Government’s response, and the high-level approach to establishing an enabling regulatory framework is a step in the right direction. Industry will have been pleased to hear explicit confirmation that “immersive technologies and content offer great potential for economic, cultural and social benefits to the UK”, and receive affirmation of the many high-quality jobs that the sector is expected to bring. Similarly, the Government should be supported in its commitment to ensuring a risk-based and proportionate approach and its pledge to “minimise excessive burdens” on the industry. Translating this sentiment into practice, the Government has already pushed back against certain proposals by the DCMS Committee, such as a recommended levy on industry to fund new research. In response, the Government said this would “disproportionately impact the SMEs and microbusinesses that comprise the vast majority of games businesses in the UK”.

Government has also provided other forms of support for immersive technologies over recent years, including through pots of funding, tax incentives, mentorship and practical support. But with a number of regulatory questions still yet to be answered (pertaining to content regulation, ethical data management, and liability, for example), the Government needs to apply the same dedicated focus to creating regulatory certainty for all immersive tech companies as it does for those in the gaming sector. Only then will the UK truly capitalise on its potential with these emerging technologies.

Topics: Immersive Tech, Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR), Technology

Comments