How countries are tackling market dominance by big tech ‘gatekeepers’

by Inline Policy on 29 Oct 2020

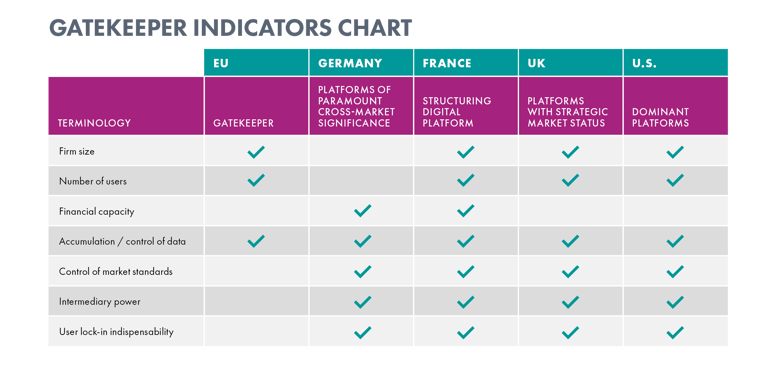

Several countries are focusing their regulatory attention on large tech platforms with the power to control the markets in which they operate, that have a structural impact on the economy, and whose products and services have become indispensable to consumers and businesses - so-called gatekeepers. They are trying to target remedies where they can be most effective and identify potential problems before they cause irreparable harm. How, exactly, do regulators define such impactful platforms? What criteria can be used? As governments and international institutions lay out the ground rules, now is the time for tech companies to get involved with the regulatory processes and help shape the rules. This blog looks at the state of play in key countries and compares their approaches in identifying gatekeepers.

UK

The UK has built a principles-based approach to large platforms in a series of reports and investigations meant to feed into future regulation. The Furman Report, a 2019 review of competition policy and the digital sector, recommended implementing new rules for platforms identified as having “strategic market status.” A market study by the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), published in summer 2020, relies on the Furman Report to define platforms with “strategic market status” as those holding a “position of enduring market power or control over a strategic gateway market with the consequence that the platform enjoys a powerful negotiating position resulting in a position of business dependency.” Identifying such platforms would rely on criteria including the platform’s share of supply in a consumer-facing market, its reach across consumers, its control over applicable market standards, and its ability to control data that is applicable across other markets.

The CMA suggests that the best way to identify platforms with “strategic market status” is to assess their compliance with three core competition objectives: fair trading, open choices, and trust and transparency. Principles supporting these objectives intend to capture potential exploitative and exclusionary behaviour, and to ensure that users can make informed decisions about platforms. More specific criteria are in development through the ongoing work of a Digital Markets Taskforce.

France

The Autorité de la Concurrence, the French competition authority, published a report in February 2020 on the idea of “structuring digital platforms” at the EU or national level. It suggests a three-step process to identify these dominant players. First, it considers the function of the entity - a structuring digital platform is an online intermediary supporting the exchange of goods, content, or services. Second, the entity holds “structuring market power” because of its size, financial capacity, number of users, and ownership of data, which enable it to control access to or functioning of the markets in which it operates. Third, the entity is indispensable to users and competitors. The Autorité then finds that such structuring digital platforms can use their position to engage in anticompetitive activity like self-preferencing, increasing barriers to market entry by controlling access to data, and making data interoperability and portability more difficult. It proposes new powers to restrict such practices, either through commitments made by a platform or requiring changes to platform conduct - and recommends that they be implemented at the EU level.

Germany

Germany has progressed on addressing platform competition to the point of legislating, with the government presenting amendments to the Act against Restrictions of Competition (GWB) in September. The draft GWB Digitisation Act draws on the work of the Commission on Competition Law 4.0, which found that clear rules of conduct for large platforms and new enforcement tools are needed. The Act includes enforcement tools for anticompetitive practices of companies with “paramount cross-market significance.” This status relies on existing dominance criteria in German law including market share and financial strength, barriers to market entry by other undertakings, the ability to shift supply or demand to other goods or services, and user access to other undertakings in the market.

The draft law lists dominant position in one or more markets, financial strength, vertical integration and cross-market activity, access to and control of data, and its intermediary power over third party users’ procurement and sales activity as the criteria for identifying platforms with paramount cross-market significance. The law would authorise the Bundeskartellamt, the federal competition authority, to prohibit certain business activities of such platforms. The draft bill now awaits further action, even as German regulators and legislators keep an eye on EU-level action.

European Commission

The European Commission is working on potential new regulations on online platforms, and recently ran a public consultation seeking views on what criteria should feed into the identification of an entity as a “gatekeeping” platform. The Commission’s working definition of large online platforms is descriptive, noting that large user bases and coverage of important, impactful services are components of gatekeeping status. A report expected in autumn 2020 will support an impact assessment of the Commission’s work on the issue by, among other elements, suggesting criteria to identify gatekeepers. These would include quantitative indicators such as user numbers, amount of gathered data, network effects, and multi-platform integration, complemented by qualitative indicators. The Commission is now preparing to unveil legislation in December with identifying criteria for gatekeeper platforms alongside both ex ante and targeted remedies to competition issues in the digital sector.

USA

Each previously discussed country has drawn lessons and ideas from the market dominance of a few firms, but the recently published US House of Representatives Antitrust Subcommittee’s report on competition in digital markets draws regulatory suggestions explicitly from its investigation of the GAFAs (Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon). While the CMA’s market study also focused heavily on the role of Google and Facebook, specifically in digital advertising markets, this report analyses the cross-market significance of these four “dominant platforms.” It identifies the features of these platforms that enable their dominance, including: network effects in their sectors, their role in connecting adjacent markets, strong user lock-in due to high switching costs, and the scale of their accumulated data. The report recommends targeted interventions on these dominant platforms, as well as strengthening antitrust laws generally - but whether legislative action is taken remains to be seen.

Next Steps

Many jurisdictions have taken steps to intervene in digital markets with some differences in approach already visible. Unlike Germany, which builds its dominant platform definition onto existing competition law, the UK and French approaches would create a new definition of dominance specific to dominant platforms. The EU is also moving to a digital-specific set of tools.

For tech competitors that rely on and are squeezed by dominant platforms, regulatory progress toward defining these entities is encouraging. It reflects a growing technical understanding by governments that the digital economy is unique and requires tailored intervention. Whether regulators can implement robust, effective remedies to anticompetitive conduct and digital market failures remains to be seen.

Now is the time to get involved with regulatory processes as governments are developing workable rules. Inline Policy can guide tech companies in engaging regulators to secure rules that preserve innovation, start-up opportunities, and real competition in the digital economy. Talk to us about your regulatory challenges.

Topics: Big Tech

Comments